Stories We Tell Ourselves:

The Work of Anne Humanfeld

essay by j. maya luz

Fig 1: Anne Humanfeld, Untitled, Watercolor, 24”x34”

Bronx-based visual artist, Anne Humanfeld, has been making art all her life, and in her telling, very seriously since the 1970’s. Her technique uses religious, historical, and anatomical imagery that suggests that the way we read signs bring us to connections, leads us to conclusions, makes us remember, makes us think, makes us feel. She is a master of layering imagery. “I’m interested in things that reveal themselves slowly through layers… layers of content, and visual layers, and layers of spirit”. (1) From a more scientific language she uses “a semantic space,… a multidimensional space that represents all responses within a modality (e.g., experience, expression)”(2). An important aspect of the work encourages individuals to create narratives that slowly appear from selection of images that are set within an aesthetic space. This gallery will illustrate some of the ways in which Anne Humanfeld’s art encourages the manufacture of narratives out of a visual language.

Most simply, Humanfeld’s work comes from the impulses of an artist to fit forms together. In her case, because of the imagery within those forms, her work inhabits a space of story-telling, and therefore the work is a kind of coded text. The viewer becomes an “investigative reader” and an agent of interpreting the “codes” of those images. Anne explains that “the images still have the energy of their former life, but now they are mine…”(3). She refers to something more general, that “our ability to make a text "mean" anything depends upon our ability to mobilize these codes”(4). In images, the “text” has many layers of meaning. Humanfeld’s work leans into “one of Saussure's crucial insights…that the sign is fundamentally relational. In other words, the relationship between the signifier and signified is arbitrary”(5). Thus, observable subject matter becomes metaphor, a “signifier” that transcends its meaning and moves towards something else, personal or collective.

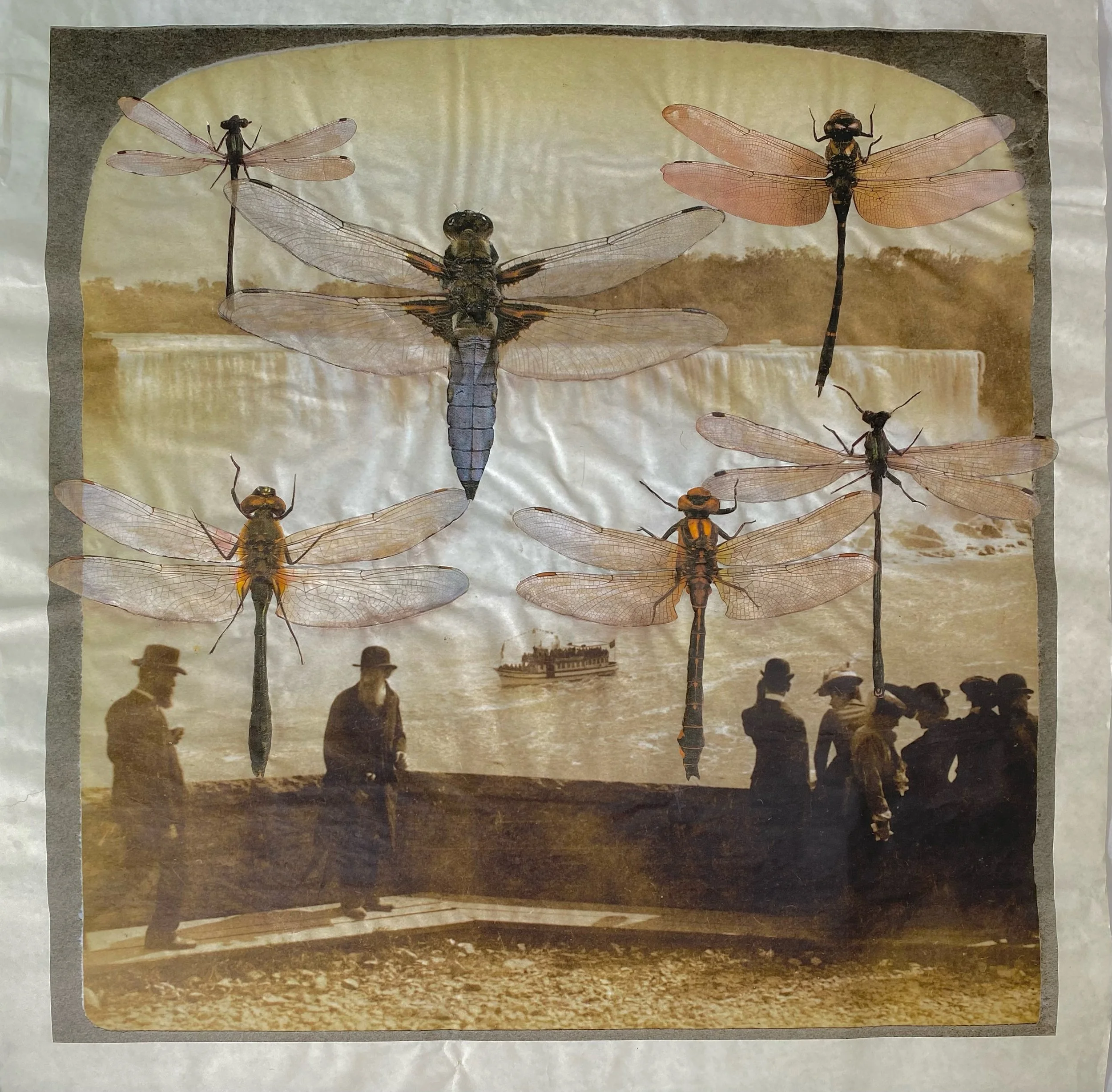

Fig 2: Anne Humanfeld, Untitled, Digital Image with Collage Elements on Mulberry Paper, 33” X 32”

One example is in Anne Humanfeld’s “Untitled, Digital Image on Mulberry Paper” (Fig. 2). We can see an image made from different photographs. As a composition, the “reader” is immediately confronted by facts from the real world. In one, we look at the arched window of one-half of a Stereo-photograph (6). We can authenticate it as a time from the past from its vintage early-industrial scene mixed with pastoral elements; its place, even if we do not know where it is, is recognizable as real. This image is set with an appliqué of bird’s eggs (the speckled eggs are from the Great Auk). These eggs share the same sepia and gray hue of the underlying image, visually merging the two. Eggs are sized from largest, at the bottom, to smallest, at the top, mirroring the effect of near to far perspective in the underlying photograph. It is an effect that creates a second window frame into the other world, as well as another plane that confuses the sense of spatial perception. What is near and what is far? These elements live in different planes, yet share a setting, which forces our “common sense” to blend them intuitively.

We labor to understand how these objects belong to each other. They become a part of a: “class of laminated objects whose two leaves cannot be separated without destroying them both” (7). The process breaks down common-sense logic: how do all these elements fit together? Our whole sense of space, time, scale and relationship has been challenged, and we find ourselves confronting a place where “semantic spaces of emotion are captured in analyses of judgments” (8), as well as emotional response. While being confronted by gaps in the story, a narrative is formed from the reader’s intuitive, and cognitive, response to make sense of a beautifully composed scene. Humanfeld has successfully placed the reader not just as the agent of meaning, but as the author of a unique narrative.

“When a stimulus exceeds our expectations in some way, it can provoke an attempt to change the mental structures that we use to understand the world” (9). In this sense, the construction of meaning shares the same impulse as the stream-of-consciousness response of a Rorschach test - in the way that randomness-plus-proximity creates association, and association conjures memories, emotions and narratives that reveal our personal mythologies.

GALLERY 1 OF 3:

On a desktop you can click onto each image to enlarge it on the screen. Hover over the image to reveal details about the work. Use the directional that will appear (on the left and right of images) to scroll through. Close the window using the “X” that you will find on the top right corner

Fig 3: Anne Humanfeld, “Styx”, Transfer Series on Canvas, 49”x56”

Those things are ‘convenient' which come sufficiently close to one another to be in juxtaposition; their edges touch, their fringes intermingle, the extremity of the one also denotes the beginning of the other. In this way, movement, influences, passions, and properties too, are communicated. Michel Foucault (10)

Humanfeld draws upon an aesthetics that rest on an artistic understanding of how multiple spatial planes interact. Using historical images that contain compositional elements of close, middle and far, like in Figures 2 and 3, the viewer’s eye is in an organized space that offers a familiar grounding for our own bodies, primarily our gaze on a horizon. Yet, it needs to account for other elements that do not conform to the rules of the first dimensional space. Under her guidance, the reader is sent into a task of free association. A task reminiscent of the surrealist’s game of “‘automatic writing’ whereby, partly on the model of Freudian ‘free association’, rapid flurries of writing were carried out in the absence of any preconceived idea” (11). In Figure 3, the depth of the plane of view in the image does not match a cubist-like organization of non-human elements, a phallus impudicus mushroom, a rock, a rabbit, a rat, a mouse, a fly. Which scale is correct? Which plane is the primary order? What is the story one intuits in this unlikely combination? Tensions throughout the work challenge the viewer to create associations that are surprising antidotes to conventional or even “satisfying” plots, leading to true interpretative investigation and therefore, agency.

Fig 4: Anne Humanfeld, “Muscle Lemurs”, Transfer Series on Glassine, 23”x35”

Humanfeld is an absent guide. Once the work is complete to her, she is content. She shares, “I’m not interested in symbols, or defining the scene. I want people to be able to come to their own responses” (12). The work is reliant upon the reader for interpretation. There is no conviction in her process that would convey the drive for a reader to take one approach to its reading over another. For example, in Fig. 4, we are presented with anatomical drawings, that could be the starting place for a hermeneutical discussion on the practice of taxonomy, how that tells us something about the history of art, and who the artist is in relationship to that chronology; the work could also be a metaphor that includes symbols for fragility, temporality, the relationship between earthbound and air born, the yearning for freedom, the cycles of life, death, rebirth.

Fig 5: Anne Humanfeld, “Nose Man”, Transfer Series on Glassine, 35”x23”

The reader is between two brains: one of logic, the other of poetics; one of the intellect, and one of intuition. It is easy to see the binaries of this place. From this perspective, it is a supposition that the binary is an adept approach to organize disorganized material; that is, material whose referential context is disturbed, and that confuses our habitual modes for finding meaning. A binary here is knowing: not-knowing. For example, in viewing Fig. 5, Humanfeld has juxtaposed a nose and a head. The nose has some kind of inflammation, it is red and bulbous. The head has a strange spatial relationship the that nose. It is a normal head, already having its own nose that is healthy. Is this a surreal image of a man-nose figure, like some sort of monster? Is this an abstract image that plays with planes of perspective, where this man’s head is twenty-feet behind this nose, and it’s a scene depicting something banal, like waiting on line in the grocery store? Does it conjure something from unconscious memory and tell a more biographical story? Is it a something completely different than any of those? In this act of locating associations to give meaning, we are, in some sense, interfacing within our own internal “fields”, as defined by Bourdieu as “domains of social life” (13); inherent within these “fields” are all the memories, experiences, sensations and associations for making meaning.

GALLERY 2 OF 3:

On a desktop you can click onto each image to enlarge it on the screen. Hover over the image to reveal details about the work. Use the directional that will appear (on the left and right of images) to scroll through. Close the window using the “X” that you will find on the top right corner

Thus, Humanfeld has placed us in liminal field, to interact with our own proficiency in meaning- making. This liminal subjective field combines all that we know and all that is unconscious. If we could think of the unconscious as another kind of field, it may be as Jung described cryptomesia:

The term is composed of two Greek words: kruptos – hidden – and mnèmè – memory. What happens in cryptomnesia, meaning ‘hidden memory’, is the following: one remembers something without realizing that it is a recollection. One is convinced that it is an original thought or intuition. Tjeu van der Beck (14)

Awake and dreaming is one way to describe this space of liminality; we are “floating” through our distinctive memory palaces, mobilized into recollection to connect image to meaning, and meaning to narrative.

Fig 6: Anne Humanfeld, Untitled Round View, Mixed Media on Unprimed Canvas, 45” Diameter

It seems to me a particularly feminine undertaking to make sense of liminality. It is worth noting that Humanfeld was a young mother of two, who began her art career in earnest after her children were grown because the demands of childrearing made it difficult to carve out an autonomous space for making work. It’s a short distance to conclude that by virtue of this that she has some experience of the liminal: organizing and responding to fluidity of change in the implicit and explicit needs of her family, and finding herself, as a human-being, within that.

Her work is charged with her own inner investigations in curating a set of forms that may, or not have meaning for her. Fig. 6 is a from a series of “Round Views” that because of their shape conjures the feminine form, a religious one, as well as a scientific one. It is a work drawn by the artist’s hand, yet the composition’s ground is arranged intentionally ambiguous as near-middle-far, like the works we have discussed earlier. The figures are also ambiguous; they relate strangely, assume gender curiously. We are coerced to understand spatial relationship, as well as gender and bodily relationship. There are no “true” answers. This game is not a game of binaries, it is a game of paradox. A game that challenges our notions of narrative and places our psyche at the center of the discourse.

Humanfeld’s work, then, is a compositional field that gives us a manner to engage with the unorganized matter of the mind.

The psyche is the starting- point of all human experience, and all the knowledge we have gained eventually leads back to it. The psyche is the beginning and end of all cognition. It is not only the object of its science, but the subject also. C.G. Jung (15)

Humanfeld’s language is a domain where the psyche is given freedom to explore. The agenda is to stimulate participation and reflexive response. The work then, is a “text”, that is also a mirror, where the “reader” views themselves in curious and surprising ways.

GALLERY 3 OF 3:

On a desktop you can click onto each image to enlarge it on the screen. Hover over the image to reveal details about the work. Use the directional that will appear (on the left and right of images) to scroll through. Close the window using the “X” that you will find on the top right corner

Notes

1- Humanfeld, Anne. “Interview with Jennifer Pliego”. August 17, 2021. New York, New York. Audio

2 - Collins, Anne, and Etienne Koechlin. “Reasoning, Learning, and Creativity: Frontal Lobe Function and Human Decision-Making.” PLoS Biology, vol. 10, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 1.

3- Robayo, Michael. “Anne Humanfeld, Artist Promo. https://vimeo.com/428791909 (2020)

4 - Smith, Philip, and Alexander Riley. Cultural Theory: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. pp 105.

5- Emerling, Jae. Theory for Art History. Routledge, 2005. pp 36.

6 - *A Stereo Photograph is a photograph produced from a camera with two lenses spaced about 2 1/2 inches apart. The result of which was a simultaneous double-image, lain side-by-side, and when printed and looked at via a special viewer, produced a 3-dimensional scene for the viewer. An interesting particularity of these images is that they compositionally represent three clear planes: close, middle, and far. This was the way that the 3-D effect was made most convincingly.

7- Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. pp 4-5

8- Collins, Anne, and Etienne Koechlin. “Reasoning, Learning, and Creativity: Frontal Lobe Function and Human Decision-Making.” PLoS Biology, vol. 10, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 1.

9- Summer, Allen. “The Science of Awe”. A white paper prepared for the John Templeton Foundation by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, September 2018. pp 3

10- Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2001. pp 18

11 - Hopkins, David. Dada and Surrealism:A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 2004. pp 17

12- Humanfeld, Anne. “Interview with Jennifer Pliego”. Nov. 23, 2021. New York, New York. Video

13- Smith, Philip, and Alexander Riley. Cultural Theory: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. pp 133)

14- van, den Berk, Tjeu. Jung on Art : The Autonomy of the Creative Drive. Taylor & Francis Group, 2012. pp 13

15 - Jung, C.G. Factors Determining Human Behavior. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1936. Print. pp 12

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Collins, Anne, and Etienne Koechlin. “Reasoning, Learning, and Creativity: Frontal Lobe Function and Human Decision-Making.” PLoS Biology, vol. 10, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 1-16.

Culler, Jonathan. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford Publishing. 2011.

Emerling, Jae. Theory for Art History. Routledge, 2005.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2001.

Hopkins, David. Dada and Surrealism:A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 2004.

Humanfeld, Anne. “Interview with Jennifer Pliego”. August 17, 2021. New York, New York. Audio

Humanfeld, Anne. “Interview with Jennifer Pliego”. Nov. 23, 2021. New York, New York. Video

Jung, C.G. Factors Determining Human Behavior. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1936. Print.

Smith, Philip, and Alexander Riley. Cultural Theory: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Summer, Allen. “The Science of Awe”. A white paper prepared for the John Templeton Foundation by the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley, September 2018.

Szczepanski, Sara M, and Robert T Knight. "Insights into Human Behavior from Lesions to the Prefrontal Cortex." Neuron, vol. 83, no. 5, 2014, pp. 1002-18.

van, den Berk, Tjeu. Jung on Art : The Autonomy of the Creative Drive. Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.